The Henson Case

Author: Owen Gallogly (College 2013, Law 2019) | February/11/2019

No single case has had as dramatic effect on the modern Honor System as that of law student Josiah (“Josh”) Henson. The saga of Henson’s case spanned over five years, beginning when Henson was reported for stealing in May 1978 and finally ending in October 1983 with a ruling by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. It drove fundamental changes to the Honor System and culminated in the first and most important confirmation that the Honor System and its procedures comply with constitutional due process.

On May 13, 1978, three of Henson’s fellow law students accused him of stealing. Henson was on the verge of graduation, and a trial was hastily convened. Five days later, Henson was found guilty and permanently dismissed from the University - two days before graduation. [1]

Henson was found to have stolen a copy of a moot court competition problem before it was released in order to gain an advantage for Virginia. At the time, Henson was serving as president of the Association of Student International Law Societies (“ASILS”), which ran the competition. Henson admitted taking the problem but maintained he was not competing and his actions were part of an internal ASILS “power struggle” to control the competition. [2] Henson argued personal animosity motivated his accusers, claiming the “hatred” between them was “legendary.” [3]

Henson appealed the guilty verdict, and in September 1978 the Honor Committee granted a new trial. Two events profoundly shaped the subsequent course of the case. First, Henson requested a public retrial. Second, Henson was accused of an additional Honor offense—lying by denying he stole the problem—to be tried alongside the original accusation of stealing.

On Friday, November 17, 1978, the Committee convened Henson’s second trial—the most extraordinary trial in the history of the Honor System. The proceedings spanned three days and comprised nearly forty hours of tense, emotional testimony. [4] Finally, at nearly midnight on Sunday evening and after five hours of deliberation, the Committee once again found Henson guilty.

The verdict shocked the University. With the press in attendance, news of Henson’s dismissal spread quickly, dominating University discourse. The bulk of the publicity supported Henson and criticized the “grave miscarriage of justice” [9] perpetrated by the “honor elite.” [10]

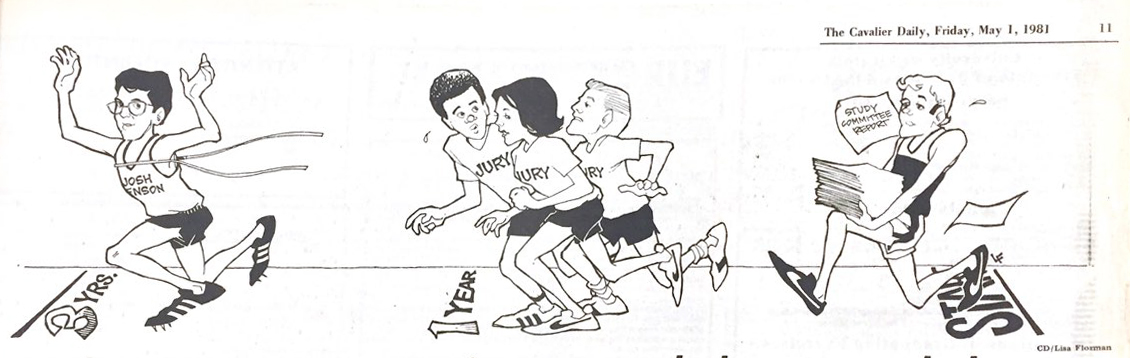

This outrage led to fundamental changes to the Honor System. At the time, juries were comprised solely of Honor Committee members. Student groups advocated for the ability of an accused student to choose a jury of randomly selected peers. Their referendum failed in the spring of 1979. But, in February 1980, the student body voted in favor of “mixed panels”—juries comprised of both Honor Committee members and randomly selected students. The Honor Chair at the time of the referendum acknowledged that “the impetus behind the jury movement was . . . the Henson controversy.” [13]

While students tinkered with the Honor System, Henson filed federal suit against both the University Board of Visitors and the Honor Committee in the United States District Court for the Western District of Virginia. He alleged that the Honor System’s procedures were unconstitutional under the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution. Read broadly, Henson’s suit amounted to a direct attack on the constitutionality of the entire Honor System.

Alongside his federal lawsuit, Henson also filed an appeal requesting a third Honor trial, citing procedural errors during the final vote on his dual charges. The federal judge presiding over Henson’s suit put the federal case on hold pending the resolution of the Honor appeal.

The ensuing Honor proceedings dragged on for over two years. Beginning with Henson’s second appeal in December 1978, the case did not resolve until January 1981, marked by numerous appeals, appeals of appeals, and even an unprecedented appeal of an appeal of an appeal. [16] Finally, the Committee granted Henson a third trial. Soon thereafter, Henson’s accuser withdrew all charges, resulting in dismissal of the case. Ironically, Henson was soon dismissed by the law school for insufficient academic performance.

Despite his inability to return to law school, Henson pursued his federal lawsuit to recover “damages and attorney fees” resulting from the Honor proceedings. [17] That pursuit was dealt a serious setback in May of 1981, when United States District Judge James C. Turk granted summary judgment in favor of the University, dismissing the case and upholding the constitutionality of the Honor System.

But Henson appealed the District Court’s ruling to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, one step below the United States Supreme Court

Finally, in October 1983, the Fourth Circuit affirmed the District Court’s grant of summary judgment in favor of the University, effectively terminating Henson’s case. A clear victory for the Honor System, the court confirmed that its student-run procedures comply with the constitutional requirements of due process. Nevertheless, the court began its discussion with a word of caution. Judge James Sprouse, writing for the three-judge panel, noted that “[i]ndividually, we might disagree with the wisdom of entrusting the Honor System’s vital controls to the hands of University students—possibly sometimes more volatile than mature,” [18] but conceded that, so long as the Honor System sufficiently guaranteed the due process rights of accused students, courts “cannot impose these views on University administrators.” [19]

And the Fourth Circuit made clear that the Honor System met that burden, holding that the “procedural steps” put in place by the Committee were “constitutionally sufficient to safeguard [an accused student’s] interest from an erroneous or arbitrary decision.” [20] In so holding, the court applauded the Honor System for providing “an impressive array of procedural protections,” specifically noting that accused students are given adequate notice of the charges against them, the opportunity to be heard by neutral arbiters, and the right to confront and cross examine their accusers. [21] The court rejected Henson’s arguments regarding his inability to have an attorney conduct his defense and Honor’s noncompliance with traditional evidentiary rules. Quoting an earlier Supreme Court case, Judge Sprouse stated that a school “is an academic institution, not a courtroom or administrative hearing room,” and it must “have greater flexibility in fulfilling the dictates of due process than a court or an administrative agency.” [22] The court went so far as to suggest that Honor’s procedural protections went above and beyond what the Constitution requires, noting that “[t]he due process clause would impose no greater obligations on the University than it placed on itself.” [23]

References

[1] Cavalier Daily, 11/14/78, “Henson to face an additional honor charge”

[2] Cavalier Daily, 11/20/78, “Honor panel convicts Henson”

[3] Cavalier Daily, 9/11/78, “Law student seeks appeal for May honor dismissal”

[4] Cavalier Daily, 11/20/78, “Tension, emotion mark three-day trial”

[5] Cavalier Daily, 11/20/78, “Tension, emotion mark three-day trial”

[6] Cavalier Daily, 11/20/78, “Honor panel convicts Henson

[7] Cavalier Daily, 11/20/78, “Tension, emotion mark three-day trial”

[8] Cavalier Daily, 11/28/78, “Henson’s innocence ‘seems quite clear’”

[9] Cavalier Daily, 11/29/78, “Henson: a ‘miscarriage of justice’”

[10] Cavalier Daily, 11/30/78, “Richardson and the ‘honor elite’”

[11] Cavalier Daily, 11/28/78, “Trennick: ‘Honor Committee Plays God’” [CHECK CITE]

[12] Cavalier Daily, 11/30/78, “Honor Committee: ‘periodic witch hunts’”

[13] Cavalier Daily, 2/26/1979, “Henson decision may force changes in honor system”

[14] Henson v. Honor Comm. of U. Va., 719 F.2d 69, 73 (4th Cir. 1983).

[15] Cavalier Daily, 2/26/1979, “Henson decision may force changes in honor system”

[16] Cavalier Daily, 1/26/1981, “Henson case leaves lasting mark on system”

[17] Cavalier Daily, 3/11/1981, “Henson to press federal court case”

[18] Henson, 719 F.2d at 73.

[19] Henson, 719 F.2d at 73.

[20] Henson, 719 F.2d at 74.

[21] Henson, 719 F.2d at 74.

[22] Henson, 719 F.2d at 74.

[23] Henson, 719 F.2d at 74.